more moments

The photo above captures an iconic moment in the history of civil rights. On March 7, 1965, John Lewis (pictured in the tan coat on the right) and hundreds of others were stopped by the Alabama State Police while attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge at the beginning of a planned peaceful march from Selma to Montgomery in protest of the death of local voting rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson. Standing next to Lewis is Hosea Williams—then Director of Southern Projects for SCLC and tasked by Dr. King to organize the march. Albert Turner, SCLC's Alabama state director, stands behind Williams. Shortly after this picture was taken, troopers attacked the marchers on what has come to be known as Bloody Sunday. Several of the marchers, including Lewis, were seriously injured. Footage of the attack was shown on ABC that evening as the network broadcast the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg.” Over 40 million Americans were watching. The impact on viewers—particularly those in the North and in Congress and the White House—was palpable. Within a week, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed the nation and called for passage of the Voting Rights Act. Five months later he signed the bill, one of the most important pieces of legislation in U.S. history. Seizing the moment makes a difference.

While THE MOMENT profiles 38 wonderful changemakers, there are numerous other activists whose stories deserve our attention. This "More Moments" page will introduce you to some of these people. If you would like to suggest someone we should feature here, please email stevefiffer@themoment-thebook.com. We will give serious consideration to all suggestions.

BRYNN JONES

Brynn Jones is a Legal Associate at March for Our Lives (MFOL) from Nashville, Tennessee. A senior at Vanderbilt University, she’s worked on issues related to activism and criminal justice reform through her work with the Vanderbilt Prison Project, advocating for Community Violence Intervention (CVI), educating young people on constitutional and legal empowerment, and writing amicus briefs that center the stories of young survivors of gun violence up to the Supreme Court level.

1. How would you define activism?

I would define activism as collective, and sometimes individual, actions taken towards a common good. Activism comes in a lot of different forms - it’s not just walkouts and sit-ins, but it’s really about creating a community that has a shared vision for a better future.

2. Was there a particular moment or series of moments that first moved you to join the fight for justice/fairness?

I always had a strong sense of right and wrong, and I think I first really became aware of that in high school. I raised a couple thousand dollars for funding rape kits, I helped facilitate an effort to get free feminine hygiene dispensers put in all the public high schools in my district, and I campaigned for local elected leaders in 2018. I think what drove me to change was this sense that things weren’t okay, that people in my community weren’t being treated well or fairly, and it drove me to participate in this way.

3. We learned about you earlier this year through your activism in Nashville. What did you do and what was the result?

In the spring of 2023, Nashville, which is both my hometown and my college town, was struck by tragedy when the Covenant School shooting happened. It was an area I knew really well, living within 15 minutes of it for most of my life. Already working for March for Our Lives as a Legal Associate, mainly interviewing survivors of gun violence, I knew the cost and the aftermath of mass violence. But I wasn’t prepared for the heartache I would feel experiencing it in my own community. Ezra Tyler—a fellow Vanderbilt student and March for Our Lives activist—and I co-organized a Nashville walk-out, which ended up having over 7,000 students across the area attend in person, with more participating from all of Tennessee, including the public high school where my mom works 30 minutes away. This action, and the coalition that we built, then were part of 3 weeks of continuous action against gun violence, including a 12-hour occupation of the State House rotunda in opposition to the expulsion of the Tennessee Three—legislators who tried to advocate for gun safety but were silenced and, in two cases, expelled from the body.

4. How did you decide your particular courses of action?

It began with the walk-out and a sense that the city and youth of Nashville needed an outlet for their grief and anger. As part of the walk-out, we invited state representative for Nashville Justin Jones to come and speak, and when he left in the middle because he was told he would be expelled and was stripped of all his committees and subcommittees, we knew we had to galvanize the coalition we had already created to support the walkout to continue our actions against the racist and fascist efforts of the House majority. Throughout the process, our main goals were centering youth voices and keeping everyone safe, with robust safety teams at essentially every single event we put on.

5. What have you learned about yourself since joining the fight?

Since starting at MFOL, I’ve seen firsthand the value of young voices and the power that we have collectively. Because of our work around the Tennessee Three, I found a community in Nashville that I haven’t had in 18 years of living in Tennessee.

6. What advice would you give to those your age who recognize an injustice and want to effect change?

I would say to any young person that sees such injustice to find other students that care, because there will be others. We have power in our collective, and finding an activist community to carry out change is the most empowering and impactful model of change for youth.

7. What should we know about what's going on in Nashville with respect to the fight for change?

The Tennessee Special Session just happened, the result of our activism in the spring, and yet again, the state legislature did absolutely nothing to keep young people safe. The best thing you can do is stay apprised of what is happening here, update your voter registration, and VOTE in your local and state elections. Local elections are where you can effect the most change in your area, and it is so important to be involved on that level.

IOWA WTF: WAVERLY ZHAO, DAVID LEE, JEMMA BULLOCK

Iowa WTF is a coalition of young people fighting discriminatory legislation through advocacy, activism, and civic engagement founded by Iowa high school students Waverly Zhao, David Lee, and Jemma Bullock. As Them.us reported in March: “Hundreds of Iowa students walked out of school as part of a “We Say Gay” protest to speak out against the state’s proposed anti-LGBTQ+ legislation.. The protest was organized by Iowa WTF and the Iowa Queer Student Alliance, (QSA) both coalitions of high school student organizers. Organizers told the Des Moines Register that students at 47 schools across Iowa walked out on Wednesday. Thus far, at least 29 anti-LGBTQ+ bills have been introduced during this year’s legislative session, according to the legislative tracking of One Iowa Action. Those include bills that would force school employees to out trans students to their parents, bills that would ban mentions of gender identity and sexual orientation in classrooms up to eighth grade, a resolution that would revise the Iowa constitution to effectively ban same-sex marriage, and more. A press release from Iowa WTF called these bills “hateful, oppressive, and un-patriotic legislation that serves to diminish the freedoms of all Iowans.”

1. How would you define activism?

Waverly: I think activism is an umbrella term for many different things. Not all activism looks the same; protest, spoken word, social media, sit-ins or walkouts, rallies, boycotts, etc, are all forms of activism. I think the anything under this umbrella, with a focus on common social issues, is activism in its own right, even if it’s small.

David: People who have been repeatedly shut down by those in power end up lacking confidence in their own voice or lose hope so they silence themselves. An activist’s role is to help them find it again and amplify it, and activism is the fight to get there.

Jemma: Activism is seeing an issue that affects not only yourself but the people around you, and doing something about it to change.

2. Was there a particular moment or series of moments that first moved you to join the fight for justice/fairness?

Waverly: My series of moments occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a Multi-Racial Asian woman, I first experienced the shift towards the Asian community following ignorant remarks made by prominent leaders within the United States, some of this behavior coming from friends and family members. Seeing the rise in Asian hate crimes, and the general hostility towards my community was difficult to say the least, but it did not stop there. After the death of George Floyd, I reached my tipping point, and I saw how my experience as a person of color was echoed in other communities. While not completely the same nor to the same extremes as in the Black community, I knew that allyship in this fight would be stronger than “oppression Olympics.” This drove me to participate in a protest for the first time in my hometown, and to join social justice groups focused on antiracism and racial equity. Since joining these groups, I have found interconnectedness and intersectionality with racial issues and other social issues, which inspired me to also begin advocating for LGBTQ+ rights, gun violence prevention, and public education.

Jemma: I've grown up in a very progressive family, both of my parents are civil rights attorneys and huge supporters of my activism, so I have just kind of grown into this "life style. But I think that a huge moment that got me involved in this specific fight against the anti-LGBTQ+ legislation from this past session was when I saw a little girl from my community speaking at the capital. She's a family friend, and she is trans. In January, she had the courage to speak out against the laws that would restrict her from being herself. She inspired me. She was brave enough to use her voice, but that isn't something everyone can do. But it's important for the messages to be spread nonetheless. I began fighting for not myself, but those who haven't been given a seat at the table.

David: During the pandemic when we teenagers were consuming news and media all day long, my algorithm was filled with protests and civic unrest that was spreading throughout the world for racial equality and the environmental crisis. Watching protestors of every identity online hand in hand made me want to jump out of the seat to run and join them. I couldn’t because of our family’s Covid policies.

3. What did you do and what was the result?

David: The first thing I did when I went back in person during junior year was to lead clubs on Social Justice and environmental sustainability. Having a organization to lead and friends to discuss the issues with was where I felt the most free at school.

Jemma: With WTF, I helped organize the walkouts. I sat down 8 days before the walkouts happened on March 1st with Emma Mitchell from IowaQSA and we started the planning. The fact that the simple plans that started that day turned into something so huge is just incredible to me, I can barely believe it some days. I specifically work on the Event Planning "Committee" for IowaWTF, so I do a lot of communication and planning for our team.

4. How did WTF materialize?

David: Waverly, Jemma, and I were each in charge of a high school club focusing on Social Justice/equity work. We had all been working on similar issues revolving around Iowa’s version of silencing education on racism, gender equality, and “divisive concepts.” We organized a walkout across the five original schools involved as a way to protest the state’s decisions to restrict our freedom of expression and education on critical social issues. We understood it would be hard to take any legislative or judicial paths to fight against the bills, so we decided that walkout demonstrations would at least show the state that students won’t stay silent when it’s their rights on the line. This year, we kept that promise of uplifting youth voices amidst the legislated discrimination against LGBTQ students and organized walkouts across the state.

5. How has WTF evolved, been received, grown since you first started it? (one of you can answer this)

Jemma: Well, IowaWTF started with just us three (David, Waverly, and I). It was a simple idea, planned during a day at the capital while we were all there together. We saw that there were issues in Iowa, specifically about youth not having a seat at the table even though our voting population is growing every year. We started out with just a six school walkout against HF 802 which prevented teachers from teaching things like CRT (critical race theory) and white supremacy, among other things. Then, with this last legislative session, we have become more known thanks to our walkouts with IowaQSA, and rallies with OneIowa.

6. How do you decide on your priorities and particular courses of action? What are your top priorities at present?

Our priorities and courses of action are often determined by the actions within the Iowa Legislature. In previous years, we focused on specifically protecting public education and raising awareness among young people about how their education was being altered unbeknownst to them. In the past, we have also called out colleges regarding attacks on students of color within the town, and because of this pressure, they were forced to increase security measures and provide support. This year, the influx of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation set the course for our action. LGBTQ+ rights will remain a priority for us until attacks against this community are halted. We also have plans to continue to fight for racial issues, public education issues, and gun violence prevention.

7. What have you learned about yourself since joining the fight?

Waverly: I have learned that I am not easily dissuaded. There have been many times when people I look up to have told me to stop or attempted to silence my voice. But I am still here, voicing my opinions and criticisms, even if it means I have to scream it for the rest of my life.

David: Being the moderate and mediator may be strategically valuable, but activism is about fighting for the people we love and when we see the change as a need rather than a desire, asking to compromise on our dreams and values or meet the opposition halfway never really means halfway for the activist that has to trek a mountain and a sea to get to the point of compromise.

Jemma: I am stronger and more powerful than I believe. I can have a bigger impact in this world than I had thought.

8. What advice would you give to those your age who recognize an injustice and want to effect change?

Jemma: Don't just sit around and wait for someone else to take the lead and try and change something. You just have to go for it, put yourself out there and try to make a difference yourself. It's going to be scary, and it might not work. But, it also might work. You might make a change. And that makes it all worth it, just the chance that something can change.

David: Fight when you can. Rest when you need it. And find a support group that fights with you and rests with you. Activism burnout takes a toll on both your professional and personal lives so make sure you take care of yourself.

Waverly: My biggest piece of advice is to begin organizing and taking action now. Even if the issue does not impact you directly, there are ALWAYS indirect effects to everything. Injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere. Do not be dissuaded by anyone if an issue is important to you. It takes a strong person to know when they are bested, but it takes an even stronger, more courageous one to continue the fight.

For more on Iowa WTF: https://www.instagram.com/iowawtf/?hl=en

INA CHADWICK

Ina Chadwick is the founder of The A Chronicles, “a safe space for the complexity of abortion and loss.” This not-for-profit created in October 2021 offers “forward-minded information for those who have been touched by the realities of abortion” and invites people to “share your firsthand experiences, learn from one another, and discover resources to help support irrevocable decisions in non-judgmental forums.” Visit: http://achronicles.org Ina is also the founder of the Connecticut-based Mousemuse Productions, which custom designs artistic programming and partners with not-for-profits to bring out the artists in every community through amateur storytelling in theaters and gallery settings and writing competitions. https://mousemuse.com.

1. Was there a particular moment when you felt you had to work for change in the reproductive rights arena?

In 1969 when I was 23 years-old juggling three babies under the age of three, I was afforded a day-a-week away from my suburban home in New Rochelle, NY, courtesy of my mother’s bankroll paying for a babysitter. All I longed to do was to be involved in meaningful activities other than homemaking and baby tending. There were no survival struggles in my neighborhood. We were privileged. Women marched for peace. Some burned bras, and others found feminism secure and nurturing enough to leave abusive husbands.

I volunteered at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in Washington Heights, NYC. At that time, The World Population Council under the direction of Dr. Christopher Tietze, a renowned researcher in contraception, was looking for interviewers to gather personal information related to his latest research: intrauterine contraception. The first line of interviews were to take place in the obstetrical ward at Sloan Hospital for Women, part of the hospital complex. My job was to visit mothers who had delivered babies the previous day. Since the lying- in was three days, the women were happy for a diversion. I spoke enough high school Spanish to communicate with them.

It was the beginning of the free love, free-wheeling 1970s. But these were mostly Puerto Rican women living below subsistence levels in nearby ghettos. Birth control? The man was in charge. A condom. As an upper middle-class young white woman, these women were my first introductions to cultures other than my own.

Besides the statistical questions about race, religion, previous deliveries, miscarriages, etcetera, the objective was to make sure the women came back to the clinic in six weeks. There, discussions of birth control would transpire if appropriate, to provide semi-permanent contraception for free. Naturally so, because most of the women I interviewed 36 hours after delivery said, “Basta! No more children.”

I spent mornings interviewing, and afternoons serving as an examining room chaperone for the male doctors. A woman in the room was a legal requirement to protect the doctor from accusations of sexual misconduct. My presence allowed the female nurses more time to give injections and dispense meds and information.

One afternoon a 40ish haggard white woman came into the clinic with her daughter, a Down Syndrome adolescent: A mother and child. The mother spoke with a serious Irish brogue. I attempted to seat the daughter outside of the examining room while preparing the table for her mother. I was surprised when it turned out the mother was asking the doctor to tell her if her twelve -year-old daughter was pregnant. She was.

The mother gasped. “This can’t be. She’s never alone. Her father is the superintendent of the apartment house we live in. She goes with him everywhere.” The room was silent. The doctor snapped off his rubber gloves.

The shock and sorrow in the mother’s eyes still haunt me. Abortion was illegal, especially since the girl was more than three months’ pregnant. “IIsn’t there an operation?” the mother stammered. I watched her pick at an already raw cuticle on her thumb.

“That is illegal,” the doctor said with annoyance. Yet he was on the board of the ad hoc committee for abortion reform for the Episcopal Diocese of New York State.

If I had any cognizance of a WTF moment then, I would’ve glowered at him. He was shaming her. I followed her out to the elevators. One of the receptionists had given the daughter a lollipop. I took a pen from the pocket of my pink volunteer’s smock and the only piece of paper I had, a gum wrapper. I wrote down the name Dr. Nathan Rappaport, Philadelphia. “Look it up in the phone book.”

In my New York City upbringing world, except for the shame and guilt, finding an abortionist was a phone call away. The money to pay for it? Also a few phone calls away. I drove home that afternoon knowing the Constitution’s rulings on abortion were being contested by a vehement constituency of women organizing lobbies and marches. I called the local offices of each political party and learned that our district’s Republican State senator had voted against repealing the laws. Was he truly representing those who had voted for him. I thought “Not.”

2. So what did you do?

I wrote a questionnaire and designed a petition that needed to be signed in order to show the senator how his personal views were in conflict with those of the people who had elected him.

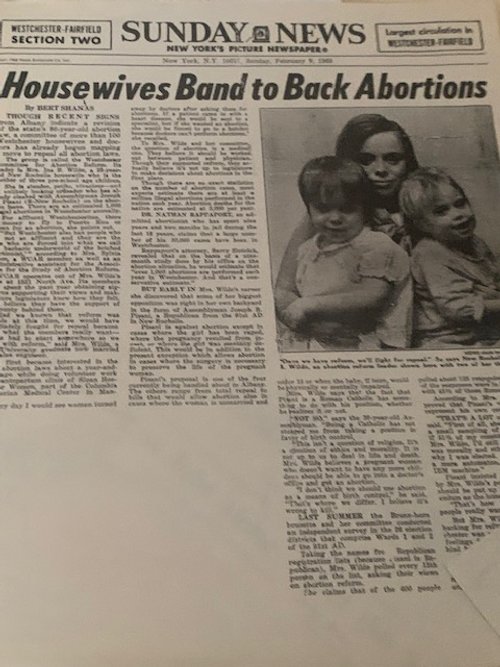

I went door to door with the petition. I tallied the answers. I aligned myself with the New York diocese ad hoc committee and became the Westchester ad hoc committee for abortion reform. With some guidance I made sure to notify the local newspapers. A grassroots movement was born.

3. Flash forward four years and we have Roe v. Wade. And then in 2022, in the Dobbs case, Roe is overturned. Is this another “moment?”

Yes. In a million years I never thought I’d have to do battle with politicians again over abortion. When the abortion issue slammed into my consciousness again, I was working on a satirical musical about the health and wellness gurus. Bam! This cannot be happening again.

Women needed to share real stories. To come out from behind shame. To share the shocking reality that one in every three women has had an abortion. The more we share, the more human we become. Our stories must be heard. Our reproductive rights should not be legislated.

I began to write another play at that moment, one that has turned into a history of all the evil myths of menstruation and childbirth. I began following the Dickensian background of a girl who in the 19th Century went on to become one of the richest women in New York City, as well as a renowned abortionist. Of course because I always hear a score, it’s also a musical. It will fall under the performance category on our website.

I love team work. It fuels my otherwise solitary writer life. I wanted a creative partner and I found the perfect woman to add knowledge and experience in creating theater for difficult conversations, death, dying and grief. Choices. Her platform is the Griefdialogues.org. We groove together. The not for profit status of The A Chronicles falls under Grief Dialogues.

Since October of 2021 when I began, the original concept,which had lots of articles and factoids, has shifted more and more to stories. Theater. Big and small. Living rooms. Health facilities.

On April 28, 2023, we are producing a staged reading in New York City at the Mary Rodgers Reading Room at the Dramatist Guild— six original ten-minute plays we’ve chosen from a contest we ran recently. We will continue to curate, produce and direct plays, radio plays also, with the subject of abortion.

We’ve got a few men playwrights in the first reading. Dark comedies, too. After-all, within the “ism” of reproductive rights activism we strive for inclusion, not sexism.

4. What have you learned about yourself through your change making efforts over the years?

I have a piece of paper I tack to my home office door, “Please, no more ideas.” Why? I often hear people say of a good idea that should be implemented: “We already tried that. It didn’t work.” I never reject ideas on the “didn’t work then” basis. I insist on looking at all the elements and not accepting the status quo. I should add that I’ve come to understand that time is not an inventoried item that can be restocked. As a result, I have to let some intriguing ideas go.

5. What advice would you give to others who may be unsure about becoming changemakers?

I think there are people who are joiners and people who are not, and the same goes for people who see things or experience tragic events in their lives and subsequently must become involved enough to overcome grief. Three of my grandchildren enrolled in a program to certify their dogs to be therapy dogs. We lost an infant granddaughter to a congenital heart defect. The nursing staff was amazing and even though the baby died, I donated my writing skills to the development department where we created fundraising brochures to further expand research for diagnostics and cures. It can be hard to make a difference individually. Look inward. Find your tribe. Volunteer if you have the time. If you don’t ,then donate money. Even a $10 a month donation to a meaningful organization can make a diffference.

IVY DOMONT

Born and raised in Highland Park, IL, Ivy Domont and her family are survivors of the 4th of July parade shooting in that Chicago suburb that killed seven people and left many wounded. Immediately following this, Ivy sprung into action, joining March Fourth's efforts to ban assault weapons federally. Now residing in Glencoe , IL, with her husband, Zack, and three children ages 3, 5, and 7, Ivy says she will stop at nothing to keep weapons of war out of the hands of civilians. Follow @March_Fourth_ on Instagram to join their efforts!

1. How would you define activism?

I define activism as acting with a purpose. For me, it’s not necessarily driven by politics, but rather by values and beliefs. I have learned that activism is further defined by its work in elevating voices that are not being adequately heard. Activism requires persistence, passion, and emotion. It is mobilized and amplified by connecting with like-minded people to become bigger than ourselves.

2. You've come to our attention lately through your work with March Fourth. Were you involved with other change-making efforts before this?

As a former elementary school special education teacher in the Chicago Public Schools, a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), and mother of three, I’ve dedicated my life, education, and career to childhood development. Since moving to Glencoe with my family, I’ve been an active volunteer with the nonprofit organization, Share Our Spare, served on the families with young children task force at our synagogue, North Shore Congregation Israel, and I remain active in both my daughter’s pre-school as well as serving on the Parent Advisory Council (PAC) in my two sons’ school district. I put my energy into early intervention efforts.

3. After the July 4 mass shooting in Highland Park, was there a particular moment or moments when you decided you had to do something? Please describe.

Here is the email I sent to marchfourthsurvivornetwork@gmail.com on July 8, 2022 at 4:47pm.

Subject: I was there...

I have attended the HP 4th of July parade since I can remember. We have our spot. We know where our friends sit. I drag my kids to this parade every year instead of going to the one in the current nearby suburb we live in. I was there with my husband, children ages 7, 5, and 2.5 as well as my parents and my sister, her husband and their 2-year-old and 2-month-old. It was supposed to be a day of celebration after 2 years of Covid cancelling the festivities. But it wasn’t. Instead, we had to run for our lives. I’m so angry that my kids had to have a mass shooting permanently imprinted on their tender childhood.

My husband and I have always discussed gun safety with our children, especially now that they are getting to an age where they are having drop off playdates. They know too much about the “bad guys” in this country and have practiced way too many active shooter drills. I am so thankful we are safe physically, but I don’t know how we will recover from this mentally. It’s still so raw, but I am gearing up to fight like hell for a change.

The email just poured out of me. The implications of the July 4th mass shooting for my own children’s development were suddenly deep and personal. How is it possible that my 2-year-old has already fled from a mass shooting shortly after taking her first steps? And what about the children nationwide who have and will be involved in and affected by growing gun violence in our country? Then, there are those who die by gun violence and won’t have the opportunity to develop at all. This was my wakeup call.

4. After this decision, what did you do?

Kitty Brandtner, a mom just a town over, was celebrating the 4th of July with her family, when the news broke. She, too, had enough. Kitty took to her own personal Instagram account to proclaim she was ready to go to Washington, DC, and scream at the top of her lungs that we have had enough of this! Enough assault weapons on our streets massacring our children. Who’s with me? It turns out lots of people were with her, and her post began to spread. That is, in fact, how I learned about her idea, which rapidly turned into a movement, a march, with a nod to July 4th as the turning point.

I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that I would be leaving my family to get on an airplane just 11 days after surviving a mass shooting to go tell my story. How was I not hiding in my bedroom under the covers? But then I learned that the community of Uvalde, which had been through the unspeakable tragedy of the Robb Elementary massacre, would be joining us in DC. For two days, I lobbied alongside them, hearing their gut wrenching stories, pleading with White House officials to get the assault weapons ban back on the table. Fast forward 9 months and I have been to Washington, DC, two more times and have been an integral part in organizing Pass the Ban events.

5. Since its creation what has March Fourth done and what are its plans for the future?

In the short 9 months that March Fourth has been around, we have become a force in the Gun Violence Prevention arena, with over 100 volunteers. What sets us apart is our singular focus in banning assault weapons federally. While we believe general gun violence prevention can be drastically improved, banning assault weapons is low hanging fruit. It costs nothing and during the time that a ban was enacted between 1994-2010, mass shooting fatalities decreased by 70%. Currently, guns are the leading cause of death for children in America, and many, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have recognized this as a public health crisis. We lobby in Washington, DC ,on a weekly basis. We are active on social media, with almost twenty-five thousand followers on Instagram, encouraging them to join the fight and protect our children. We are simply asking the House and Senate to do their jobs and listen to the majority of Americans who want to ban assault weapons federally. Currently, we are imploring Senator Schumer to call S.25, the assault weapons ban, for an accountability vote. Show us who in Congress wants to keep schools, grocery stores, parades, shopping malls, and clubs safe, and who is in favor of choosing assault weapons over lives.

While March Fourth keeps plugging away with government affairs, we have created Aftermath, our non-profit 501(c)3 sister organization. The mission of Aftermath is to connect communities impacted by mass shootings, provide resources and supports, and advocate against gun violence. We fell on the name Aftermath because we found that after a mass shooting occurs, the news cycle moves on fast, leaving victims and survivors to pick up the pieces. We have created an Aftermath Advisory Council to help guide us in creating a blueprint for communities that are impacted by mass shootings whereby we can help them navigate resources and supports that are equitable, purposeful, and culturally responsive. I feel passionate about this work. Not only do I serve on this advisory council as a survivor, but I am also the lead program developer for Aftermath.

6. What have you learned about yourself through this process?

I learned what I’m certain others have learned before me: when confronted with an existential threat, I found resources within me that I hadn’t before used. Traveling to Washington, DC, to meet with and talk about my experience with legislative officials and the news media was never in my playbook. Perhaps, it was being a mom that gave me that extra fight.

I continue to learn from those that have walked this path before me, and I do my best to inspire others to use their voice for change. The 4th of July sprung me into action, March Fourth gave me the platform, and everyone I have met along the way has given me purpose.

7. What advice would you offer to others who face a sudden traumatic event in their community--be it from gun violence or anything else--and want to mobilize?

Be kind to yourself. After experiencing trauma, there are a variety of ways people cope. Advocacy is what is healing for me.

KRENICE RAMSEY

Krenice Ramsey is a civil rights attorney with the U.S. Department of Education who did her undergraduate work at Spelman College and earned her JD from New York University School of Law. She grew up in Evanston, IL, and after a period away returned home. She currently lives in Evanston with her husband Derrick and their young daughter. In 2018, she and Derrick founded the not-for-profit, Young, Black & Lit. https://youngblackandlit.org

1. How would you define activism?

Activism, simply put, is taking action to effectuate change.

2. You've come to our attention lately through your work with Young, Black & Lit (YB&L). Were you involved with other changemaking efforts before this?

I am a proud board member of the (Evanston-based) James B. Moran Center for Youth Advocacy, an organization which provides holistic social work and legal advocacy for youth. In this role, I have supported the Moran Center's efforts to provide critically important support to some of the community's most vulnerable individuals, including working directly with community institutions (e.g., school districts, police) to ensure the rights of youth are respected and protected.

3. Was there a particular moment or moments when you decided you had to do something and the idea for YB&L was born?

About five years ago, I walked into a major bookstore to find children’s books featuring Black girls as a birthday gift for my niece. After about 30 minutes in the store searching shelves full of books featuring animals and children who looked nothing like my niece, I left empty-handed and saddened that there were likely few bookstores my niece could walk into and feel seen.

Determined to make sure that children like my niece had easy access to children's books featuring Black characters, I started making small personal donations of books to local youth-serving organizations. When my husband and Co- Founder, Derrick Ramsey, learned of my efforts, he believed that my small efforts could grow into something bigger. With my determination and Derrick's vision, Young, Black & Lit was born.

4. After this decision, what did you do to actually create YB&L?

The first step we took to formalize YB&L, was to establish the organization as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Next, was the work of identifying children's books that centered, affirmed, and reflected the various experiences of Black people. After identifying the types of books we wanted distribute to the community, we needed to find a way to pay for the books - a critically important piece! We started reaching out to our networks, spreading the word about our mission, and thanks to the overwhelming generosity and support of our networks we began receiving donations and applying for grants to support our work. Finally, we started putting action to our mission by donating books monthly directly to youth, schools, and youth-serving organizations.

5. How has YB&L evolved/grown since its creation?

When we started in 2018, we were donating 50 books per month to youth, schools, and youth-serving organizations in the Chicagoland area. Today, we are donating up to 3000 books per month to youth across the country. We have seen significant growth in our reach, but our mission remains the same - increasing access to children's books featuring Black people and Black culture.

6. What have you learned about yourself through this process?

I have learned that what you may think is a small idea can turn into something wonderful. I had no idea when I started giving away a few book donations in my community that we would be giving away thousands of books years later. Every time I see a child get excited about the books we offer, our work is affirmed. I have learned that I have the ability to make an impact and I will carry that with me in all of my efforts.

7. What advice would you offer to others who have a moment when they realize that change is needed to remedy an unfair or unjust situation and are unsure whether to act or not?

Do something, no matter how small you may think it is, to remedy the situation. Sometimes that may look like you speaking out and using your voice, other times it may mean using your resources (e.g., money, access, power), and sometimes it may be taking a back seat and elevating voices other than your own who represent the community most directly impacted by the unfair/unjust situation. Whatever the "something" looks like, do it. Small actions can lead to big results.

DAHLIA BRESLOW

Eighteen-year-old Dahlia Breslow is a senior at Northampton (MA) High School. She is Co-Chair of the Northampton Youth Commission—the official city body dedicated to representing young people. The Youth Commission, comprised of young people ages 13-18, works directly with elected leaders along with local community organizations to draft legislation and lobby for policies that benefit young people. Dahlia has also been involved in working for justice in the areas of voting rights, reproductive rights, and the environment.

How would you define activism?

Activism is using your voice or elevating others’ voices to create change.

Can you pinpoint a particular moment that first moved you to work for something you believed in?

My moment was when I met other people my age who shared my strong beliefs and realized that in joining together, our power for change was strengthened.

Would you briefly describe some of the major instances where you have worked for change and what moved you to work on those particular issues.

During my first year of high school, I joined the Youth Commission, a youth-led body within the Northampton City Government. The Youth Commission had already been working for several years on an initiative to lower the municipal voting age to sixteen as part of the national Vote16 movement. Initially, I was actually resistant to the idea. I was pretty quickly convinced by looking at the voter turnout of Takoma Park, MD, the first city in the US to lower their voting age to sixteen. The city’s voter turnout clearly showed that eighteen-year-old first time voters turned out less than sixteen or seventeen-year-olds voting for the first time. Sixteen was the better age. Together with my civic-minded peers, I devised a campaign strategy, wrote editorials for our local newspaper, spoke at city council meetings, and gathered a thousand petition signatures downtown. In June 2020, we testified before the Massachusetts State Legislature Election Laws Committee. Throughout, I heard the word “no” far too many times. And yet, I pushed through. Young people deserve the right to vote because we have a major stake in the issues on the ballot.

In terms of climate change, an issue close to my generation, we know we will carry the burden of salvaging our world once the damage is already done. I want sixteen and seventeen-year-olds in my city to be involved in making decisions that directly affect our lives and futures—decisions regarding our elected officials, emissions policies, and funding for our schools.

What advice would you offer to a young person who experiences a moment and is debating whether or not to become involved to eliminate an injustice/work for change?

Talk to your friends, your classmates, your peers. You are not alone in feeling injustice. There is a strength in numbers that will aid you in working for change, but moreover provide you with a support system for the frustrating and hopeless times.

What do you see as the most important issues which your generation faces?

First and foremost, climate change. Secondly, my generation has the difficult task of repairing polarization. I think that no matter how strongly our belief systems might clash with someone else’s, it is imperative to listen and try to understand their perspective. True change isn’t accomplished by interacting only with those similar to you, but by working with those who are different.

How optimistic are you about the future ?

I am an optimistic person by nature. What makes me feel hopeful is meeting and hearing the stories of wonderful people. As much as there is in the world to make me lose hope, I’m certain that there is more good.

Is there a particular person whose life in working for change inspires you?

My dad inspires me because he taught me to listen and respect others even when I may disagree with them.

PRIYA SHAH

As a Chicago creative and entrepreneur, Priya Shah has built a network of artists and collaborators dedicated to igniting social awareness and change through art and imagination. Shah began volunteering in developing countries at a young age, which inspired her to fill the gap between business and the social sector. She went on to earn degrees in both Accounting & Finance from the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, using her studies as an opportunity to deepen her understanding of diverse cultures and perspectives through international travel.

After graduating she went on to work at Big Four Accounting firm, Ernst & Young, and finally Groupon, leading strategic planning in Operations. Her purpose took shape in 2011 when she founded The Simple Good, a non-profit with the mission to connect the meaning of good from around the world, empowering youth to become positive activists through art and discussion.

How would you define "activism" or "activist?"

An activist is someone that is inspired by moral conviction to bring about social change.

Was there a particular moment or series of moments when you became an activist--left the sidelines and tried to address a wrong and effect change?

I've always inherently been an activist as I've always been fighting the oppression put upon me because of how I was born into the world, whether I realized it or not. It was after seeing how prevalent oppressive mindsets do exist in the world which leads to so many tragic outcomes, I increasingly moved towards figuring out how to actively move the needle through my work and social spaces.

When that moment (or moments) presented itself, what specifically did you do? What form did your activism take, and what was the result?

In every stage of my life, I was looking for opportunities to learn from the world before I acted. In University, I studied abroad around the world and volunteered in slums to better understand global histories and communities that have been pushed aside. When I got my first corporate job, I used resources within the firm to contribute to Chicago communities both inside and after work. I eventually realized there was a huge gap on how effective community impact is made - which is through cultural competency and intention. I took the step to bridge that gap by starting my own nonprofit, The Simple Good.

What was the inspiration for founding The Simple Good? Was there a moment when the idea came to you?

I grew up with hurdles including being a minority, a woman and being born a with one hand; in fact, I remember one evening in India, I was 9 years old and I overheard my aunt say this to my mother in our native tongue, "She could have touched the moon, if only she was not born like that." Instantly I thought, "Why couldn't I still touch the moon?" I was born without a left hand and because of that there was a lot of doubt, shame and oppression towards my aspirations. Having one hand was never something I constantly thought about. Therefore it was never a barrier for me. But growing up, you realize others definitely do take it into account. I learned that how people perceive you is sometimes how obstacles are created. We are not born into the world with them, people create them. But for this reason, they can be overcome.

I actually come from a corporate background but have been very fortunate to have traveled to many different parts of the world. I have met and connected with diplomats to beautiful kids in many different and often difficult circumstances. Through these intersections I realized we all worry about many of the same things. We cry and get angry about the same actions, and at the end of the day, the same things are good to us. Whether it be a sunset, a kind gesture or a smile, the fundamental element of good is the same to all of us, and that is what connects us as human beings.

So naturally after having meaningful interactions such as these, being in a corporate space for so long felt very limiting to me. As an outlet, I ended up starting a blog where I posted different pictures from my travels and the various “simple good” stories I discovered through them. I then asked the world to submit their own photos - and virtually overnight the blog went viral. I started receiving submissions from places like Spain, Brazil, China. A newspaper in Italy even wrote about us! It was amazing to see how my small truth could spark a global reaction of discovering goodness within their own lives and then share it with each other. This taught me the world was looking for a simple way to connect to one another. In an interconnected world, our small actions have large outcomes; this needs to be fueled towards positivity. So the story of how my non-profit got started was precisely through this. It started with the blog.

Then what?

After the strong response online, I knew I wanted to bring this online discussion to the ground - back home to the States, where the same desperate poverty I saw abroad was in my backyard. I grew up in Chicago, and it is still one my favorite cities in the world. But we suffer from our violence and poverty - and this largely impacts our youth. But there are simple things that can create hope even in these environments.

It all started was by being moved by the ‘simple good’ the world had shown me, and moving this understanding to a 3rd and 4th grade classroom in one of our communities on Chicago’s South Side. We implemented a curriculum to take students on a journey to discover different meanings of good through art. The impact was profound. Over a course of only a few weeks, a classroom that was full of kids repeating negative things they were hearing in their environment, suddenly became a calm, thoughtful group of students that began to develop their own series of questions about good, such as ,”Who do you love?” This was the beginning of our very first pilot program, which has now expanded into a full arts residency program that has spanned the world reaching almost 6000 youth since founding the organization.

What advice would you give to someone today who has a moment and is debating whether or not to act?

The only way to build the world you want for yourself is by taking action. Even the smallest steps help you move towards your possibility.

Is there a particular book you would recommend to aspiring activists?

I love James Baldwin, but in general love reading philosophy and poetry that truly makes you examine the human spirit which is what challenges you to intentionally take action as an activist.

JONATHAN EIG

It seems fitting to launch the “More Moments” page on Martin Luther King Day. And who better to conduct our first Q and A with than the acclaimed journalist Jonathan Eig, who has previously written biographies of Muhammad Ali, Lou Gehrig, and Al Capone? This May will see the highly anticipated publication of his years-in-the-making biography, KING: A Life. Eig is pictured below in his Chicago home.

How did Dr. King define “activism” or “activist?”

The nice thing about King (or one of the nice things) is that we don’t have wonder what he would say about most things. He covered a lot of ground himself. He told us over and over again that activism was a requirement of citizenship and a requirement of religious faith.

He hardly ever gave a speech or sermon in which he didn’t say something to this effect. Here’s just one example: When he quoted the Old Testament prophet Amos, which he did many, many times, what did he say? “Let justice flow like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” He’s saying justice comes from God, and it should flow like water, like a mighty stream, if only we stop obstructing it. That’s why the first word is so important. Let. “Let” is the call to activism. It says we must do our part to make justice flow like water.

Want more? “If you can’t fly, then run. If you can’t run, then walk. If you can’t walk, then crawl. But whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward.” And while I hesitate to quote “I have a dream,” because it’s over-used, what is the dream but a call to activism? Even dreams require action or else they go unfulfilled, or, worse, they turn into the nightmare that King began to describe shortly before his death, an America riddled with racism and overrun with materialism, poverty, and militarism.

Was there a particular moment or series of moments when King first decided he had to become an activist, to get off the sidelines, and participate in the fight for social justice?

If I had to pick a date, I’d say December 5, 1955. King wanted to be a college professor. He thought he’d preach a few years in the South and then get a teaching job. But Montgomery pulled him in. He was asked to serve as spokesman for the bus boycott, and he addressed a huge crowd that night at Holt Street Baptist Church.

He spoke so beautifully, so powerfully, that the people would have followed him anywhere. That was the beginning of his new career as an activist preacher. And once he got started, and once he saw he was needed, he couldn’t turn back. He saw he had a chance to attack Jim Crow and fight for justice. Preaching and teaching were no longer going to be enough. He felt he had a greater calling, a calling that came specifically from God.

When his moment presented itself, what did he do? What form did his activism take and what was the result?

He put his life on the line, for one thing. He faced death threats, violent attacks, arrest. He made himself the face of the movement. He set aside any personal ambitions. He took on the audacious task of leading millions of Black people across the country. Oh, and he was 26 years old at the time all this began.

After serving as the face of the movement in Montgomery, he made the critical and courageous decision to go beyond, along with Ralph Abernathy and others, to attempt to replicate the success of that movement across the country. They created the SCLC with the idea that Christian love could be a force as strong as the NAACP’s team of lawyers in the fight for morality and fairness. He built and organized this operation from scratch, with the help of a few veteran activists such as Bayard Rustin and Ella Baker. Did I mention he was only 26?

How did that initial experience of joining the fight influence his activism over the coming years as more moments presented themselves?

King was always adapting. When the Albany Movement {an attempt to desegregate Albany, Georgia in 1961} fizzled (at least in some people’s eyes), he took a deliberately different approach in Birmingham. But he did more than learn from his failures; he also thought about how he could use his influence to extend beyond the areas in which he had already enjoyed success.

So instead of continuing to focus on voting rights after 1964-5, he set his sights on attacking racism and segregation in the North, even though he knew it would cost him some of his most important supporters, and he took up the fight against the war in Vietnam, even though he knew it would damage his relationship with LBJ. Every time he could have stepped back, he doubled down.

What advice do you think Dr. King would give to someone today who has a moment and is debating whether or not to act?

If you are fighting for justice, equality, for the spirit of love, for God, he would say: Act. Every time. And, once again you don’t have to take my word for it. He said: “Any real change in the status quo depends on continued creative action to sharpen the conscience of the nation and establish a climate in which even the most recalcitrant elements are forced to admit that change is necessary.” He also said, “The time is aways right to do what is right.”